A holiday essay for you about one of my favorite thought criminals, Mary McCarthy. Happy new year!

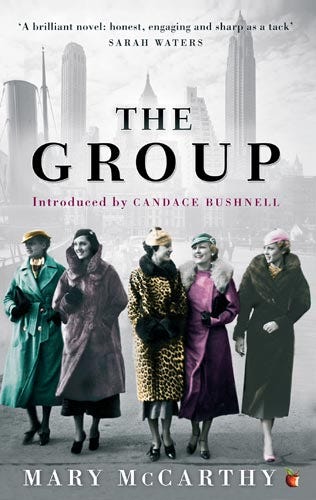

Perhaps it escaped your notice, given everything else that’s been going on, but this year marked the 60th anniversary of Mary McCarthy’s iconic novel The Group. Published in 1963, it revolves around eight graduates of the Vassar College class of 1933, a cohort of which McCarthy herself was a member. Though the book was dismissed by critics as shallow ephemera, its frank depictions of the lives of educated, pedigreed women, including unmarried sex with drunken strangers, made it a sensation. It sold 300,000 copies in its first 18 months in print and was made into a much-hyped 1966 film directed by Sidney Lumet and starring a young Candice Bergen.

Among the more prominent characters is Kay, whose wedding to an erratically employed theater director named Harald is the opening scene of the novel. (The uncommon Norwegian spelling is no accident; McCarthy herself married a New York City actor named Harald Johnsrud shortly after graduation.) There’s also Dottie, who at Kay’s wedding meets an inebriated artist named Dick and loses her virginity to him in his squalid apartment the very same night. Dick has eyes for Lakey, a gorgeous aristocrat who’s off to Europe to study art history, but he settles for toying with Dottie, telling her she’d be even more interesting to him if she took care of the birth control side of things. “Get yourself a pessary,” he says as she’s leaving his apartment.

There’s also Norine, who’s sleeping with Harald because her own husband is impotent; Priss, an earnest social justice activist inconveniently married to a Republican; Libby, an ambitious publishing assistant who eventually becomes a successful agent; Polly, a hospital technician of modest means who has an affair with Libby’s married, psychoanalysis-obsessed boss before her own mentally ill father comes to live with her.

I could go on, but arguably the central character of the novel is that pessary, the Depression-era version of a diaphragm. It’s the detail that tends to be most remembered by readers and functions as something of a controlling metaphor about control itself—and the lack of it. Most doctors would only prescribe them to married women, but Dottie procures one using her Vassar connections, after which she goes directly from the doctor’s office to a park bench where Dick has promised to meet her. He never shows up, and she is so distraught she leaves the device under the bench and flees home to Boston.

And so the women stumble and tumble through the political and social muck of the era. They chase and are chased by men, sometimes marrying those men and sometimes sleeping with men married to other women. They climb the professional ladder, exult over fine furnishings and Art Deco apartments, have miscarriages as well as babies, learn about psychoanalysis, give their pets names like Nietzsche, and drink and smoke with an abandon that is as enviable as it is alarming.

Despite their steamer tickets and places on the Social Register, many are fashionable supporters of the Communist party, and in the lead-up to the war they’re becoming slowly deranged by politics. By the end of the novel, Kay’s feverish political consciousness—along with her frustration with her philandering husband—lands her in the psych ward (the husband puts her there, as only a husband could then). When she’s finally sprung, she’s so worked up that she manages to fall nine stories to her death from the coveted Art Deco apartment.

“I’ve been working on a novel for years, it’s about eight Vassar girls, called The Group,” McCarthy said in a 1963 Vogue interview. “It’s about the idea of progress. There are these eight girls that go through the book and who are subjected to all the progressive ideas of their period, in architecture, design, child-bearing, home-making, contraception and so on. It’s kind of a technological novel about the woman’s sphere.”

Then as now, the woman’s sphere was considered a lesser literary subject than, say, the battlefield or the political sphere or even literature itself. Since McCarthy had carved out a place for herself as a merciless critic of other people’s books—the “lady with the switchblade,” according to Life magazine—the knives came out for her in turn. An unnamed reviewer called her “an intellectual on the surface, a furniture describer at heart.”

Norman Mailer dismissed the book as fluff, describing the characters as women “whose communal odor is a cross between Ma Griffe and contraceptive jelly.” Perhaps worst of all, McCarthy’s ostensible friend, the critic Elizabeth Hardwick, wrote an eviscerating parody of The Group under a pseudonym. Hardwick’s husband, the poet Robert Lowell, called McCarthy’s book a “very labored, somehow silly Vassar affair.”

What is a Vassar affair exactly? As a graduate of the Vassar class of 1992, I can only say it’s whatever you make it. Which is to say it’s whatever you go on to do with the person you make yourself into at Vassar. Though I wouldn’t get around to reading The Group until my 40s, I spent many hours in my dorm room reading McCarthy’s short-story collections as well as autobiographies like Memories of a Catholic Girlhood, How I Grew, and Intellectual Memoirs. I read them not just for pleasure but as training manuals. For all my participation in the woman’s sphere—I, too, coveted a 9th-floor Art Deco apartment—I didn’t want to be Kay or Polly or Libby. I wanted to be Mary McCarthy.