Maybe it’s because my chief adversary has always been my body, but I’ve never had a problem with my face. I’ve actually always liked my face. For most of my life, my operating assumption has been that my face is quirky but reliably cute, occasionally even pretty. The defining feature is my chin, which ranges from gently triangular to downright pointy, depending on where I am in the five-pound window of weight I tend to slide around in. From as early as I can remember, I was told I had a heart-shaped face and that this was a good thing. I was also told by my mother that while my body would always be a problem (given that her body was a problem, it would only follow that mine would be too, since in her mind we were the same person), my face was pretty and I was lucky not to have to worry about it.

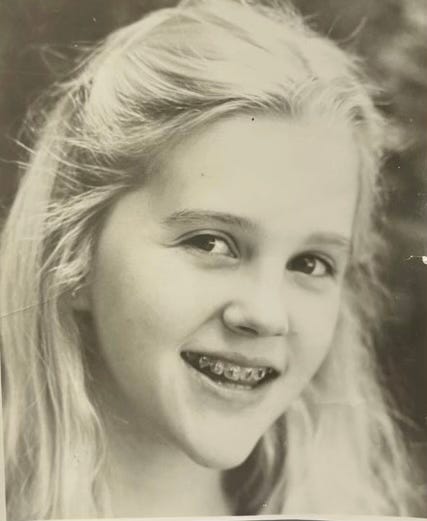

And so for the better part of fifty years, I didn’t worry about my face. In fact, I enjoyed it. Throughout my entire adolescence, I didn’t have a trace of acne. Though my narrow jaw required multiple tooth extractions and several years of orthodontia, including an appliance that widened my upper palate, I even enjoyed having braces. Back then, braces were what signaled to the world that you were no longer a child but a bona fide teenager. And since I wanted nothing more than to grow up and be a mature person in the world, all that metal in my mouth felt like an on-ramp to freedom.

Although my extremely fine, extremely straight hair presented some frustrations, I mostly dealt with this by having a short haircut, which I felt I could pull off due to the high quality of my face. I never wore makeup and was well into my twenties before it even occurred to me that I should maybe put on some mascara and lipstick if I was going to a wedding or formal event. As far as I was concerned, my skin was flawless, my cheeks were rosy, and my eye color contrasted nicely with my hair color, so what was the point of makeup? Besides, I had more important things to think about, for instance how flawed my body was.

Decades later, the situation has somehow reversed itself, or at least shifted the contents of its neuroses. While I mostly tolerate my body, I suddenly hate my face. My chin, which invited comparisons to Reese Witherspoon’s from almost the moment the actress first appeared on-screen, now strikes me as requiring its own zip code. My nose, which I never gave a second thought to, looks slightly wider than I’d ever perceived it to be. Though my skin is still decent and I seem thus far to have avoided the jowls and turkey neck that all of my contemporaries are obsessed with, the heart shape that was once so central to my identity appears to have hardened into something closer to a downward-pointing kite.

Sometimes when I look at myself, I think I look like Jay Leno in drag. Other times, I feel my wide nose and wider eyes make me resemble a Muppet. In some of my lowest moments of moral and physical self-appraisal, I am visited by the chilling notion that at some point when I wasn’t paying attention, I went from being a pretty girl to being a “handsome woman.” The horror this elicits makes me ashamed of my vanity, which in turn makes the horror that much worse.

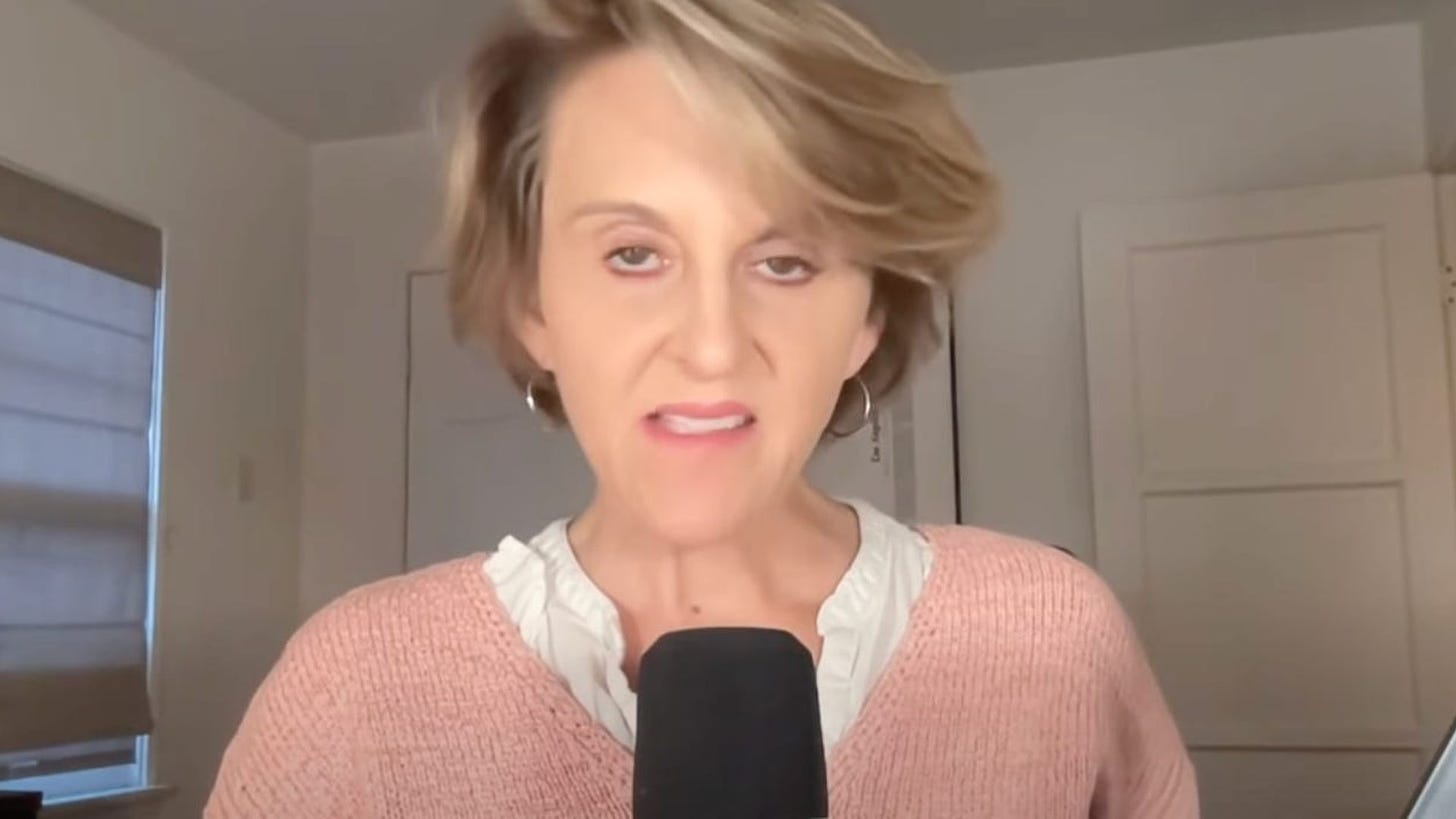

When I say “look at myself,” I’m not talking about looking in the mirror. I’m talking mostly about looking at myself on the computer screen, often within the confines of a 16:19 ratio box with 1,080 pixels. This is not a flattering medium for anyone, but when you are an aging woman who looks like a Jay Leno Muppet, it’s a hall of carnival mirrors.

I’ve been podcasting for the past three years and, last summer, since one podcast is not enough, I started another one with Sarah Haider, a woman who is more than 20 years my junior. She is brilliant, opinionated, and unapologetic in her worldview, which is occasionally hilariously at odds with my own. She is also young and beautiful, which only became a factor early this year when we accepted that it is a truth universally acknowledged that you can’t grow your audience unless you surrender to video and YouTube.

So now, every week, instead of sitting around in our sweats or pajamas and recording three hours of conversation about the news of the day, we put on decent clothes, apply makeup, style our hair, declutter our “studio” backdrops, and fire up the expensive lights and cameras we were advised to purchase in order to look professional. Then we attempt to talk about current events and philosophical concepts without veering out of the frame or, in my case, rocking back and forth, which apparently is something I do while talking that I hadn’t the faintest awareness of for more than half a century. The most memorable (ideally outrageous) moments of these conversations are then isolated and cut into promotional video clips in which our heads appear in silhouette cutouts alongside episode titles like Hateful Nerds Need Love, Too and Babies, Breast Implants, and Disgust.

From a vanity standpoint, it’s hard for me to say which is worse: the promo clips, which tend to capture my face in a freeze frame of unflattering mouth contortions, or the videos at their full length, which, as far as I’m concerned, are about 20 percent me looking sort of okay and 80 percent my own personal reenactment of The Ring, the classic (2002) Gore Verbinski paranormal psych thriller about a videotape that causes death to anyone who looks at it.

My podcast partner, for her part, has dewy skin and the kind of lustrous dark hair that cameras love. Unlike me, she doesn’t need reading glasses to see the screen, so she’s not constantly adjusting them and shifting her gaze around to try to avoid glare from those expensive lights. I try to avoid the YouTube comments lest I spot something that will bruise my ego even beyond the injuries I already inflict upon it. But when I do peek at them, they’re full of viewers extolling my partner’s youth and beauty. (Did I mention that she also hates the way she looks? Do I even need to mention it?)

I hate that I’m forced to wear my reading glasses on the YouTube podcast, but recently I discovered that there’s something even worse: not wearing them. Tasked with recording a quick introduction that did not require reading anything off the computer screen, I removed my glasses, imagining the audience gasping in surprise; “Why, Miss Jones, you’re beautiful!”

When I watched it back, I was shocked. My eyes looked tired and even lopsided. My chin looked even more prominent than usual, and not just because I didn’t have the benefit of eyeglasses to draw attention in the other direction. Out of nowhere, my chin seemed to be showing traces of marionette lines, giving me the vague appearance of a Chucky doll. This is not a podcast intro, I thought. This is a horror movie.

The truth is, my face has always been a complex proposition. I might have passed most of the time for “conventionally attractive” (blond hair helps), but I’ve always been aware that the attractiveness is entirely dependent on the angle. I have one of those faces that can go from pretty to homely with just the slightest tilt of the head. Generally speaking, I look decent facing head-on, but the profiles get tricky. That’s where my chin abandons its post at the bottom of that heart shape and becomes something more like a rock protrusion. “A Habsburg chin,” someone called it on social media years ago, commenting on a photo accompanying some article I’d written. I didn’t know what they meant until I made the mistake of looking it up and seeing they were referring to the “mandibular prognathism” common to the dynastic Austrian family and thought to be a result of inbreeding.

For all I know, there could have been inbreeding somewhere in my not-too-distant heritage, as my father’s paternity was effectively unknown, and no one in the family ever seemed interested in finding out more. My chin is my father’s chin; there’s nary a trace of my mother there. This is a dark thing to say out loud, but the reason I hated my body and not my face is because my mother saw herself in my body but not my face.

Though my fat upper arms were an heirloom passed down on her side—if you must pose for a picture in short sleeves, always bend your arms so they look slimmer, she told me when I was six—my chin was out of her jurisdiction, not her fault or responsibility. And since my father’s self-loathing did not extend to his appearance, it never occurred to me to dislike my chin. In fact, I liked my chin precisely because it looked nothing like my mother’s. Since everything about her appearance was (according to her) wrong, anything that wasn’t like her was, by definition, right.

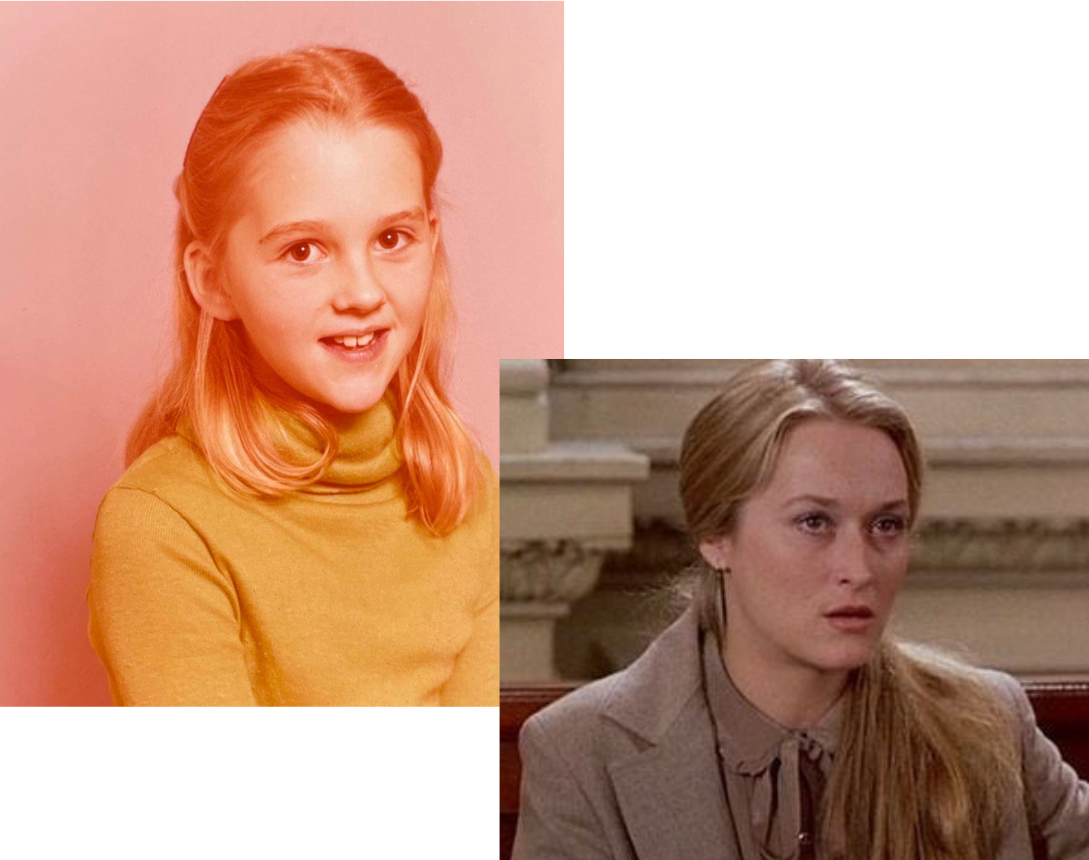

So even as I did constant battle with my body (the details are so typical as to be barely worth mentioning), I made peace with my face. When I was nine years old, a friend’s parents went to see Kramer vs Kramer and subsequently decided that I looked like Meryl Streep. Looking at pictures of myself from the time, I can almost see what they meant. More importantly, even though I did not grow up to look like Meryl Streep, I decided at some point in my early twenties that I was cursed—or blessed—with what I deemed “Meryl Streep Face Syndrome,” which is what you have when you can look strikingly beautiful from one angle and then almost monstrously misshapen from another.

That’s not to say I was ever strikingly beautiful or that Meryl Streep has ever been close to monstrous. But let’s be honest; some faces are simple and some are complex. And simple faces can withstand a far greater range of conditions. Sometimes those conditions are called “regular photo with no filter.” I once saw a series of tweets from a portrait photographer expressing exasperation and even sorrow at the way her subjects reacted to their own images. So accustomed were they to the trusted filters and reliable head tilts of their own selfies that seeing their actual faces reflected back at them—sometimes on actual film—was so shocking as to be devastating. People have no idea what they look like anymore, the photographer observed. Worse, they have no idea what people look like anymore. It’s not unlike what you hear about the effects of pornography. We’ve become so inculcated by digitally enhanced images that our blueprint for sexual excitement is effectively a piece of AI. Faced with a flesh-and-blood human being, actual disgust can set in.

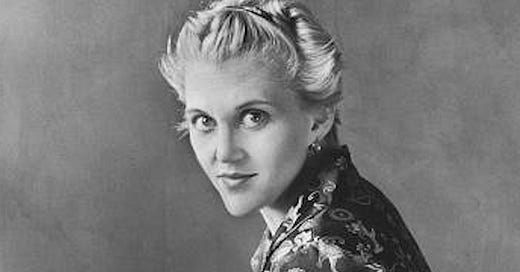

But whatever happened to that old adage about everything looking better in black and white? (In “Kodachrome,” Paul Simon sang that everything looked worse, but it was obvious that he meant the opposite.) Film cameras could be merciless in more ways than one, but when they were good to us, they were very good. As a young author, I posed for steely black-and-white portraits—on real film—many times. This was at least half the point of being an author. The sessions lasted for hours, and you had no idea what you looked like until such time as you saw that now-artifact known as a contact sheet. I’m pretty sure I hated the vast majority of shots on the vast majority of contact sheets, but the handful that made the cut are worth a thousand of even the best digital photographs in the eras that followed.

In 2005, in what is still one of the most awestruck moments of my life, the revered portrait photographer Marion Ettlinger, known for her photos of famous authors, called me and asked if she could take my picture simply because she liked my writing. The resulting photos, one of which I posted at the top under a provisional allowance from Getty Images that I’m pretty sure is okay for 30 days, fall into the category of the photo itself being beautiful but the subject being kind of strange looking. I love the photo even though I kind of hate how I look.

The above photograph, probably taken in 2000, appeared on the back of my first book, My Misspent Youth. Shot by the photographer and filmmaker Alix Lambert, it’s a black-and-white image of my 30-year-old self standing in front of a wall of graffiti in downtown Manhattan. It’s a close-up, so you can’t really see the graffiti, but it’s there in spirit, which is to say it’s there in a way that you can only capture with real film. Also, I’m pretty sure I’m wearing no makeup whatsoever.

Twenty-plus years and many lifetimes after the fact, a man I was dating stood in my apartment and pulled the book off my shelf. “Whoa, I recognize this photo,” he said. “At a bookstore in Boulder in 2001. I remember seeing it and thinking, ‘Now, that is someone I’d like to know.’”

“Did you buy the book?” I asked.

“Well, no,” he said.

That is someone I’d like to know. What more can you ask of a face than that? Sure, it’s nice to be the object of desire, admiration, even envy. But the highest compliment that one human can pay to another is an interest in actually knowing them. In 2015 or so, after I did a literary event on a stage, a woman came up to me and asked if she could paint me sometime.

“The planes of your face are very unusual,” she said. “It would be a challenge to paint you.”

I knew this was a form of flattery—sort of. I also knew that what she was saying was that I looked good from certain angles and dreadful from others and that this represented a kind of aesthetic puzzle. I think she handed me a business card, which I’ve long since lost, but I think of her every time I saddle up for yet another YouTube recording. I have a Post-it above my desk on which I’ve written STAY STILL, CHIN DOWN in giant letters. The less head movement, the less often I’ll veer into a bad angle. The more I can keep my chin down, the more I can avoid looking like a Habsburg with a YouTube channel. As for my glasses, they’re never coming off again.

I haven’t even mentioned Botox and dermal fillers. What can I say? I’ve both done them and not done them. If I could afford it, it’s possible I’d do them more, but at the end of the day, I don’t actually think they make much of a difference. I have a dermatologist in New York with whom I have a friendly enough relationship that she feels comfortable cheerfully berating me for not loading my face up with Juvederm.

“Look at this,” she’ll say, pulling up one side of my face. Then she’ll point to the other: “And look at this. See the difference?”

“I guess so,” I’ll say. But I honestly can’t see the difference, partly because I don’t have my glasses on.

How has it come to this? How, after building a career for 30 years, has my value been reduced to a thumbnail photo and the appraisal of barely-post-adolescent YouTube commenters? I know, I know . . . that’s just the sound of my distorted thinking. It’s not really like that. No one is actually saying that my intrinsic value is only as high as the quality of my appearance on a video box. But somehow, we’ve arrived at a moment in which artists and thinkers of all ages are subject to appraisals not just of their ideas but of their physical selves, often poorly lit and awkwardly framed. And while I know that for anyone born in the past 30 years, this is all completely normal and will remain so forever, I still believe that art and ideas, especially when they’re good, deserve to be experienced with a little mystery and imagination. Which is to say, without looking at their creators and wondering why they picked such an ugly shirt or whether they look like a Jay Leno Muppet. We can do that on our own.

And this is why when Meghan Daum posts an article, I skip past all those other saved substack articles and read hers first.

this dovetails nicely with an absurd Paulina Porizkova instagram caption I read this morning that said something like “there’s no representation of aging.” what? I’m literally watching everyone age! in real time! on the internet!